This Series looks at the process of the phantasm engendering thought. A narcissistic wound or trace of castration causes desexualized/neutral energy to create a metaphysical/cerebral surface resulting in thought. This metaphysical surface of thought is invested by the sexual surface of the body (sublimation) and by the objects of the depths and the heights (symbolization).

Deleuze uses a metaphor of a romantic couple to conceptualize sexual sublimation. The phantasm's formula: from the sexual pair to thought via castration. It may prove useful to approach this Series like a Zen koan. The phantasm originates in the void. He last wrote about the void in the "19th Series of Humor" in connection with Zen. I suggest giving it a review (p. 137 in the 1990 edition; p. 141 in the Bloomsbury newer edition). There seems a great deal of movement, cycling back and forth and feedback loops implied as thought metamorphosizes and reinvests in itself through sublimations and symbolizations. The phantasm always goes back to an originary phantasm and carries it along to wherever it's going. It constantly changes. Due to all this looping, Deleuze says the phantasm is the site of the eternal return. The writing returns to earlier concepts like the void. Again, by connecting the trace of castration with the crack of thought from the "22nd Series: Porcelain and Volcano" mentioning the writers Lowry and Fitzgerald from that Series. He references the "21st Series of the Event" when talking about death toward the end. There is an inflexion point in this Series when Deleuze changes from talking about the little thoughts of the internal dialog to more creative, problem-solving thoughts. This point is where he mentions the "phantasm's path of glory." It does it with "the incorporeal splendor of the event as that entity which addresses itself to thought, and which alone may invest it – extra-Being." I.e. sense. Splendor, in the hermetic sense, can be researched in my blog: The Hermetic Transmission of Francois Rabelais.Monday, July 24, 2023

Friday, July 14, 2023

30th Series of the Phantasm

Deleuze first presents his interpretation of the concept of the phantasm and its relation to sense in this Series. He comes from a Freudian point of view saying that psychoanalysis is the science of the event. He goes into three characteristics of the phantasm in this series and continues the discussion of it in the next Series.

1. The phantasm is the resultant of an action (outer) and a passion (inner) and represents a pure event. 2. The relationship of the ego to the phantasm 3. The phantasm finds expression in the proposition. It inheres in the infinitive form of the verb. The Aion is the neutral infinitive for the pure event. Objects in the depths he calls simulacra; objects in the heights = idols; objects at the surface = images. Freud's book "Totem and Taboo" is the great theory of the event. You can read it here.Tuesday, July 4, 2023

The Hermetic Transmission of Francois Rabelais

Member of the NEW TRAJECTORIES WEBRING

Happiness is reached when a person is ready to be what (s)he is.

– Desiderius Erasmus

Rabelais, once more, laid down the philosophical principles

which determined the destiny of Shakespeare in literature

and Bacon in science.

– Aleister Crowley

All references are to the 2006 Penguin Classics edition of Gargantua and Pantagruel translated and annotated by M.A. Screech. This edition contains five books ordered chronologically by publication date. This makes the second book Gargantua; some editions place it first in the sequence given that it takes place before Pantagruel's birth. In modern parlance, Gargantua is a prequel. Since the 19th century, most scholars, including Screech, don't believe Rabelais personally wrote the fifth and final book. The anonymous writers writing under his name do a good job of imitating his style.

Gargantua and Pantagruel, by Francois Rabelais, distinguishes itself as the first mass-produced popular novels that combine literature with philosophy and mysticism in the hermetic fashion. The carrier wave for this transmission is humor in every form imaginable: satire, slapstick, scatalogical, salacious, sexual, irony, wordplay, nonsense, parody, dark, burlesque, ribald, bawdy, juvenile, farcical, facetious, surreal, etc. A massive dose of sugar that makes the medicine go down or be unnoticed. Rabelais was dubbed the Laughing Philosopher by Mary Patricia Willcock in her 1950 biography of him, a well-deserved epithet he shares with the ancient Greek writer Democritus. These novels should be in the Guinness Book of World Records for the most extensive, detailed, erudite, cultivated, fetid, malodorous, putrid, stinking and rank variety of fart jokes in the entire output of human literature. Rabelais celebrates both physics and metaphysics, but above all, JOY.

These five multileveled novels comprise, among other things, a survey and criticism of philosophical, religious and ethical knowledge from the West, ranging in time from Ancient Greece to the beginning of Renaissance Europe. It's presented as a pastiche of fable and folklore replete with proverbs, adages, sayings, quotations, etc. Sources drawn upon include Plato, Plutarch, Pliny, Aristotle, Aesop, Avicenna, Homer, Hesiod, Cicero, Seneca, Virgil, Ovid, the Bible, Erasmus, Cornelius Agrippa, and many others, some of them totally obscure to the modern reader.

Roots

Rabelais' funny bone taps into roots going back to the dawn of civilization. The oldest joke known to humankind is a Sumerian fart joke: They had a saying: Something that never happened since time immemorial; a young lady did not fart in her husband's lap.

His most prominent, guiding light, his mentor, was the humanist philosopher Desiderius Erasmus who died a few years after the initial publication of Pantagruel. Erasmus' best known book is In Praise of Folly, a satirical look at society, in particular The Church. Both Rabelais and Erasmus were inspired by the Greek satirist Lucian, in particular his short essay (or letter) To One Who Said to Him 'You Are a Prometheus in Words.' He wrote it in response to a critic who complained that he put "comic laughter in philosophic solemnity." Up until Lucian, it was unusual to combine Comedy with thoughtful Dialogue. As an example, Lucian points out how philosophy was ridiculed in Aristophanes' satire, Clouds, with Socrates reduced to calculating how far a flea can jump in one leap. Clouds symbolize philosophical hot air in that play.

Erasmus begins In Praise of Folly with a short poem, On the Argument and Design of the Following Oration which closes with:

"So here,

Though Folly speaker be, and argument,

Wit guides the tongue, wisdom's the lecture."

He starts the oration proper demonstrating, why humor? In a ridiculous costume and speaking as Folly:

"HOW slightly soever I am esteemed in the common vogue of the world, (for I well know how disingenuously Folly is decried in the world, even by those who are the greatest Fools) yet it is from my influence alone that the whole universe receives her mirth and jollity: of which this may be urged as a convincing argument, in that as soon as I appeared to speak before this numerous assembly all their countenances were gilded over with a lively sparkling pleasantness: you soon welcomed me with so encouraging a look, you spurred me on with so cheerful a hum, that truly in all appearance, you seem now flushed with a good dose of reviving nectar, when as just before you sate drowsy and melancholy, as if you lately come out of some hermit's cell."*

* This vivifying life-force, the reviving nectar, exemplifies what Gilles Deleuze refers to as humorous nonsense making a donation of sense in his magnum opus, The Logic of Sense.

Erasmus was a close friend of Sir Thomas More, known for his book Utopia, a term he coined. Both writers translated different works of Lucian into Latin. The Latin title of In Praise of Folly, Moraie Encomium puns off of his friend's name: it can be translated as In Praise of More. Moria, in Greek, translates to Folly. Puns run throughout In Praise of Folly. Like fart jokes, Gargantua and Pantagruel multiply puns wherever possible. A great thing about this edition is that M.A. Screech notes which puns in French don't come through in translation.

Erasmus loved and collected proverbs, over 4000 of them, which he also commented upon; some are still in current use like: "in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king." He published them under the title Adagia - adages. One or another of these adages, sometimes several at a time, get referenced by Rabelais in nearly every chapter.

Both Rabelais and Erasmus were ordained as Catholic clergy and both eventually got excused from having to perform their priestly duties to pursue scholarly activities which in Rabelais' case also involved becoming a Doctor of Medicine. They were known as lay priests. Rabelais had also joined both the Benedictine and Franciscan monastic orders. Religious upheaval was in the forefront during their era. The Protestant Reformation began in 1517 c.e., less than twenty years before the first edition of Pantagruel. Both these scholars skewered the Papacy, monastic life and other aspects of The Church while avoiding taking sides in the religious schism of their times.

Contemporary Influence

The enduring effect of Rabelais on entertainment culture, even in small ways, goes largely unnoticed these days. How many fans who have seen Pink Floyd play live post-Animals album realize that the flying pig at their concerts appeared in the third book of Pantagruel? A satire on semiotics, two characters communicating nonverbally through ridiculous signs and gestures happens twice in the Pantagruelian adventures. A skit riffing off the same premise would turn up some 400 years later in an episode of Monty Python and the Flying Circus called Michael Ellis. This episode strongly influenced writer Robert Anton Wilson as I document here. Studies exist looking at the influence of Rabelais upon Monty Python. Someone writing as Dr. Karma calls Rabelais the father of modern sketch comedy in the piece The Quintessence of Rabelaisian Pythonesque.

The humor in G & P for the most part, appears very low-brow, often scatalogical. As a medical Doctor, Rabelais became fascinated and intrigued by every aspect of the body and all its working parts. In Rabelais and His World, Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin formulates two interconnected concepts, literary modes he calls Carnival and the Grotesque Realism. The former has developed "an entire language of symbolic concretely sensuous forms" that challenge dominant cultural assumptions through humor and nonsense. He defines the latter as pulling down all that is noble and ideal to the material level. Pointing out, for instance, how Rabelais metaphorically employed various functions of human anatomy to illustrate political conflict. Bakhtin begins his study with a very interesting quote from Alexander Herzen: "It would be extremely interesting to write the history of laughter."

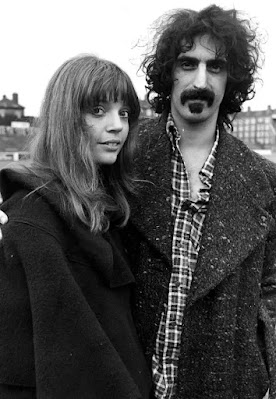

From his very first album, Freakout, musician and composer Frank Zappa showed a distinctly Rabelasian bent for combining bawdy, often sexually explicit, humor with social satire. This risque sensibility runs throughout Zappa's oeuvre. Some prime examples come to mind: "Dinah Moe Hum" and "Camarillo Brillo" from the Over-Nite Sensation album, the" Don't You Eat the Yellow Snow Suite" and "Cosmik Debris" from Apostrophe, the film 200 Motels, "Why Does It Hurt When I Pee", "Crew Slut" and "Catholic Girls" from Joe's Garage to name just a few.

In a 2008 thesis for her Master of Arts degree titled Frank Zappa and Mikhail Bakhtin: Rabelais's Carnival Made Contemporary, Sarah Hill Antinora calls "Joe's Garage: Acts

I, II, and III, a carnivalesque attack on organized

religion, the Church of Scientology, rock and roll's

obsession with groupies, and, above all, censorship." Pulling an anecdote from an interview of Zappa by David Fricke in Rolling Stone magazine, Antinora demonstrates his musical comedy:

"Just as many of the carnivalesque writers did before

him, Zappa often mocks with love. For example, he used to

play Led Zeppelin's "Stairway to Heaven" note for note, until the guitar solo. His complete brass section performed

the guitar solo instead."

Gail and Frank Zappa

Zappa employed Pauline Butcher as his platonic, live-in secretary for four years in the late '60s/early '70s. Along with his family, Zappa lived in a large log cabin in Laurel Canyon, LA, formerly owned by cowboy star Tom Mix. Seven other people lived there along with Frank's then family of four. It wasn't uncommon for rock star royalty to drop in and pay him a visit. Butcher recounts how Robert Plant gave his wife Gail a book by Aleister Crowley on "the otherness of life." The book made its way to Frank. "I think he was strongly influenced by Aleister Crowley. I think he got quite a few ideas from Aleister Crowley's book." (Quoted from a You Tube video in which Butcher was asked why Zappa didn't read newspapers or pay attention to the news.) Aleister Crowley has been more influenced by Rabelais than anyone else except, possibly, James Joyce. More on that ahead.

Hermeticism

Among the arts and sciences which it is affirmed Hermes revealed to mankind were medicine, chemistry, law, art, music, astrology, rhetoric, magic, philosophy, geography, mathematics (especially geometry), anatomy and oratory. Orpheus was similarly acclaimed by the Greeks.

– Manly P. Hall, The Secret Teachings of All Ages

Encounters with all these fields of learning occur in Gargantua & Pantagruel though often subject to the ridicule of parody or satire. Rabelais provides a broad reckoning of the knowledge of his time and didn't appear at all shy with giving an opinion except where it could get him in trouble. Contemporary authors that have attempted an encyclopedic scope of all known knowledge include James Joyce with Finnegans Wake and Ezra Pound's The Cantos. Robert Anton Wilson had ambitions to write his own epic exploration to be called Tale of the Tribe. In its five volumes, Gargantua & Pantagruel portrays a Renaissance tale of the tribe.

The strict definition of Hermetic thought adheres to those writings bearing the authorship Hermes Trismegistus. A much broader definition is adequately summed up in the full title to Hall's opus quoted above:

An Encyclopedic Outline of

Masonic, Hermetic, Qabbalistic, and Rosicrucian Symbolical Philosophy

Being an Interpretation of the

Secret Teachings concealed within the Rituals, Allegories

and Mysteries of All Ages

Hermetic also indicates a tightly sealed container, as in hermetically sealed. This metaphorically applies to Hermetic philosophy as many of the symbols or allegories don't easily give up their knowledge. The symbolism acts as a sealed container holding information or wisdom inaccessible to the profane. They need to be unlocked before their secrets get revealed in gnostic apprehension. Hence the term "occult," meaning hidden, gets accurately applied to Hermetic thought. Rather than anything macabre or scary, garish or ghoulish, occult simply means hidden.

Rabelais immediately lets us know he intends a Hermetic transmission. In the second paragraph from "The Prologue of the Author" to the first book, he implores the reader to drop all his daily tasks to learn his novel by heart, in case printing presses should fail so it can be passed on to their descendants as a "religious cabbala." Those two words don't appear in the first edition, circa 1531 but do turn up in the definitive edition of 1542 which include a number of revisions and variations he added, many of which were done to avoid the (sometimes fatal) wrath of the Authorities. It seems possible he added the "religious cabbala" description to clue people in to the esoteric side found therein. Cabbala would explain his odd and apparently deliberate use of long, strangely specific numbers. "The Prologue" starts by addressing "Knights most shining and chivalrous ..."

Pantagruel is a giant coming from a long line of giants. Tales of giants were popular then. His father is Gargantua, a name Rabelais picked up from an earlier folk tale by an anonymous author called the Great and Inestimable Chronicles of the Enormous Giant Gargantua. He tells us the meaning of Pantagruel – Pan in Greek means all; gruel means thirst, hence all thirst or always thirsty. It's suggested Rabelais named him that because he wrote it at the end of a four year drought in Europe. In the book, he writes that "his father imposed that name on him ... wishing to signify that at the hour of his nativity all the world was athirst, and foreseeing in a spirit of prophecy that he would one day be the Ruler of the Thirsty-ones." This is immediately followed by another sign: when his mother was giving birth, before he came out of the womb "there first sallied forth from her belly sixty-eight muleteers, each leading by the halter a mule laden with salt; after which there came nine dromedaries laden with smoked bacon and ox-tongues, seven camels with eels, and then five-and-twenty wagons with leeks, garlic, chibols and onions." All things that will drum up a great thirst.

We find Cabbala in the title of the first book:

PANTAGRUEL

The horrifying and dreadful

DEEDS AND PROWESSES

of the most famous

PANTAGRUEL

KING OF THE DIPSODES,

Son of the Giant Gargantua.

Newly composed by Maître Alcofribas Nasier

Dipsodes means thirsty. Maître translates as master. Alcofribas Nasier is an anagram of Francois Rabelais. The initials of the author's name as presented here spells MAN. This aligns with the Tale of the Tribe aspect of this work. Looking at the pseudoynm he chose: in the Bible, "Al" represents God. "Nasier" is close to the Arabic name Nasir which means friend or supporter.

Speaking on the issue of Rabelais' attitude toward free-will, translator M.A. Screech writes in his Introduction: In Pantagruel (following the Latin Vulgate) men must be 'God's helpers'. By the time of the Fourth Book, following the original Greek, men must be God's co-operators... The technical name for the doctrine of Rabelais is synergism ('working together').

Cabbalists have a penchant for all kinds of puns, wordplay and looking at things in reverse. Seen this way, Pantagruel means both always thirsty and a thirst for All. "Drink" becomes a watchword throughout the novels, as if a central sacrament; what they drink, what quenches their thirst is wine. However enthusiastic any of the characters become about the product of the vine, it never seems to get consumed in excess, we never find a celebration of inebriation or drunkenness. Wine, of course, symbolizes intoxication of the innermost, intoxication of spirit, as in the blood of Christ. In the Fourth Book, Rabelais uses the symbol of a winged Bacchus borrowed from the 2nd Century Description of Greece by Pausanius to represent spiritual intoxication. This sign caught on to become included in many Renaissance emblems.

Hermes Trismegistus

This legendary Egyptian figure, who most likely didn't literally exist as a single individual, gets directly mentioned by our author multiple times. But then again, it seems every ancient learned character imaginable gets name checked by Rabelais, whether in praise or criticism, to make most erudite his raunchy tale of the tribe.

A large part of the Third Book concerns Panurge trying to decide if he should get married or not. Getting cuckolded (cheated on) is his biggest fear. The character of Panurge serves as a foil to Pantagruel; it's his earthly, more human and base side. If you think of Pantagruel in the position of Thoth – the Egyptian God who brought writing and magic to humanity, cognate with Hermes, then Panurge would be the Ape of Thoth – the animal aspect.

The insight that humans can develop abilities, visions and empathies going far beyond ordinary capacity lies at the heart of Hermetic thought. Among other things, a hermetic transmission intends to show through metaphor, allegory and directly, how to go about unlocking hidden potentials in the human biological machine. Gargantua and Pantagruel are giants and come from a long line of giants: allegorical for expanded human potential. Not only are they giants, they're shape-shifting giants, their size varies in different situations.

The adages, jokes, proverbs, puns, fables, allegories, etc. injected into the satire communicate a multi-level didactic course of learning in Pantagruel. As mentioned above, the nonsense makes a donation to the sense of the instruction. Aleister Crowley received this so well that he made salient parts of it a cornerstone of his School. There's an excellent section in Book 1 Ch. 8 where Gargantua writes a letter on how he wants his son to be educated. He is to develop his capabilities and knowledge to the max. He tells him to learn multiple languages, Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Chaldean. "I want you to learn all of the beautiful Civil Texts by heart and compare them to moral philosophy." ..."Then frequent the books of the ancient medical writers, Greek, Arabic and Latin, without despising the Talmudists or the Cabbalists; and by frequent dissections acquire a taste of that other world which is Man." Along with much more in the curriculum.

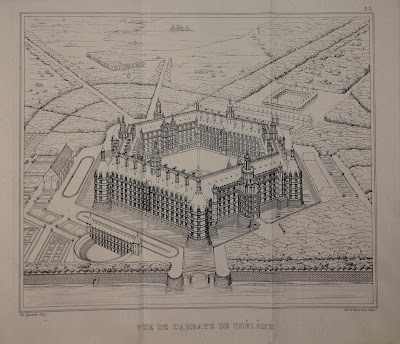

The Abbey of Thélème and Aleister Crowley

After a long, eventually victorious war that takes up much of Book Two, Gargantua rewards those who fought beside him with land and riches. That won't do for the heroic Frere Jean des Entommeures aka the Monk. Gargantua offers to make him Abbot of one or another or both of two distinguish Abbeys but the Monk turns him down and requests that he be allowed to establish his own abbey to his own devising, contrary to all others. The last six chapters of Gargantua concern the building of the Abbey of the Thélèmites and how it's to be run. It's Rabelais' ideal, utopian formulation of a Monastery.

The Cabbalistic numerology of its financing and construction appears obvious. Six and multiples of six play a prominent role. The building is to be hexagonal and its to be six stories high. Each angle has a solid round tower measuring sixty paces in diameter. The specificity of the financing suggests numerology. I'm amused that Rabelais includes how the budget is to be balanced. The initial outlay is: "twenty-seven hundred thousand, eight hundred and thirty-one Agnus-dei in ready coin" supplemented with sixteen hundred and sixty-nine thousand Sun-crowns and as many golden Pleiades raised from tolls on the river Dive" until its completed. A perpetual annual endowment for maintenance and upkeep comes to twenty-three hundred and sixty-nine thousand, five hundred and fourteen rose nobles derived from ground rent. Both men and women are equally welcome in this utopian religious order though they abide in separate living quarters. "In each of the ante-chambers stood a crystal looking-glass, framed in fine gold and surrounded by pearls; it was large enough to give a true reflection of the whole person."

The Abbey of Thélème

Do what thou wilt because people who are free, well-bred, well taught and conversant with honorable company have by nature an instinct – a goad – which always pricks them to virtuous acts and withdraws them from vice. The call it Honor. In a note, Screech points out that Rabelais' definition of honor matches that of a theological concept called synderesis - the guiding force of conscience. This force can be cultivated and strengthened. In the story, the freedom and liberty given by 'Do what thou wilt' results in the Thélèmites all trying to please each other.

Aleister Crowley felt that Rabelais forecast a new aeon of Life, Love, Liberty, Laughter and Light some 370 years ahead of time. Crowley endeavored to actualize what Rabelais had imagined. He set up his own Abbey of Thelema in Cefalu, Sicily to put his principles into practice. As he saw it, these principles came from outside ordinary humanity. The man Crowley did not write, but rather received the Law of Thelema; it was given to him for humankind by an outside source. As the story goes, a "praeter" (beyond) human Intelligence named Aiwass dictated the the Law of Thelema to him in what became known as The Book of the Law. Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law. In the 16th century, M.A.N. (Maitré Alcofrybas Nasier) had prophesied its own next step.

Crowley analyzes and comments upon Rabelais' prophecy in the article, The Antecedents of Thelema reprinted in The Revival of Magick. It's remarkable that a force starting out virtually, as an idea in a piece of literature, becomes actualized into the world. Crowley found other prophetic synchronicities in Gargantua; he found his name and magickal motto there. The final chapter (56) is called "An enigma uncovered amongst the foundations of the Abbey of the Thélèmites." This enigma appears as a long, apocalyptic visionary poem by the Court poet Mellin de Saint-Gelais (a real person) Rabelais tacked in there supplemented with his own intro and outro. It concludes:

Then we shall all with certain knowledge see

The good and fruit brought forth from patience' tree:

To whom, before, most suffering did grieve

Shall be allotted most, shall most receive

Such was the promise. How must we revere

Him unto the End does persevere.

Crowley's first motto, his name, in the Golden Dawn, Perdurabo, means 'I will endure unto the end.'

Crowley received the Book of the Law ("shall most receive"). This looks like a prediction, to me.

The Monk, head of the Abbey of Thélème, asks Gargantua what he thinks this engimatic poem means and gets the answer: "divine Truth." The Monk disagrees, he sees it as a description of a tennis-match. "The end means that, after such travails, they go off for a meal! And be of good cheer!"

The Roman Catholic Church looms large in G & P. Both Rabelais and Crowley knew the Bible inside out and used quotations from it to suit their own purpose. Both also sharply criticized The Church and its bureaucracy though it held much more danger to do so for Rabelais therefore he appears more guarded; guarded, but far from silent in his criticism. As we shall see, Thelema wasn't the only thing Crowley inherited from Rabelais.

Another obvious connecting link between the two is humor, both writers were extremely funny. It's not always clear when they intend to be serious or when a serious point lurks behind a joke, or when it seems pure, nonsensical farce. Robert Anton Wilson calls Crowley the funniest mystic he knows.

The Final Oracle

"Do you have gullets so daubed, paved and enamelled

that you did not recognize the savor of the bouquet of this deifying liquor?"

As the story of Pantagruel and friends continues, it increasingly incorporates mythology into the hermetic signal. Most scholars agree that the posthumously published Fifth Book was by Rabelais in name only. It seems one or more Adepts saw the underlying hermeticism in the first four books and not only took up this line of thought, but brought it forward making it blatantly obvious. The writing has as much erudite reference and imitates the voice of Rabelais well, but perhaps with a little less subtle wit in the humor. However, the Alchemy, Magic and Cabbala loudly states right off the top "Here I Am!" in the Prologue to the Fifth Book ("I will wait upon the masons, boil up the pot for the masons and, since I cannot be their comrade, they will have me as a listener – I mean an indefatigable listener – to their most excellent writings.") proceeding to a slowly rising crescendo that climaxes with an archetypal journey down through the Underworld leading to an encounter with the final oracle, the oracle of the bottle.

Panurge's question of whether to marry or not eventually sends the gang to the oracle of La Bouteille on a distant island. Chapters 33 - 47 of Book 5 concerns their adventure when they get to that island. I consider this essential reading for students of Thelema; the chapters are short. We discover the bottle is "trismegistical." The High Priestess Bacbuc brings Panurge to the bottle telling him to listen to it for a word. She does a ritual to bring forth the Word. Panurge hears "a sound such as is made by bees when they are born from a young ox duly slaughtered ...

Whereupon was heard this Word: Trinck.

'Might of God!' exclaimed Panurge. She has split – to tell no lie, cracked! Thus in our lands speak crystal bottles when they burst by the fire.'" Trinck is a German command: "Drink!" The Word of the final oracle is Drink!, a main theme of Pantagruel (thirsty for All.) German is used for the onomatopoeic sound of a bottle cracking, and perhaps also for the cabbalistic significance of the letters.

As mentioned above, the great majority of chapters in Gargantua and Pantagruel refer to one or several adages by Erasmus whose first book, In Praise of Folly, he wrote to communicate Wisdom. Aleister Crowley composed a lengthy epistle to his magical son called Liber Aleph vel CXI, The Book of Wisdom or Folly. It comprises 208 short, adage-like chapters of a page, or often less. The last one is: On the Final Oracle. It concludes: "I cry aloud My Word, as it was given unto Man by thine Uncle Alcofribas Nasier, the Oracle of the Bottle of BACBUC, and this word is TRINC." Crowley then changes it to TRINU, saying that was the ancient spelling, to make it add up to 666. As he testified in Court: "'The Beast 666' only means 'sunlight'. You can call me 'Little Sunshine'." It's a solar number as 6 = Tiphareth. 6 x 6 = 36. Adding the numbers 1 - 36 = 666. This agrees with the Cabbala in the story where Trink is called "that Word of beauty." Liber Aleph enumerates as 111. 111 x 6 = 666.

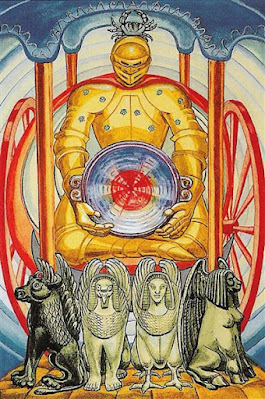

Crowley also used TRINC as an adage for The Chariot tarot card in the 1925 publication, The Heart of the Master. He used this adage again in The Book of Thoth, one of the last books he wrote:

VII

The issue of the Vulture, Two-in-One, conveyed;

This is the Chariot of Power

TRINC: the last oracle.

It's outside the scope of this essay to unpack all the Qabalah here, it seems central to Thelemic magick. The chariot carries the Holy Grail. Suffice to comment briefly from The Book of Thoth: The Holy Grail in this card is described as: " . . . of pure amethyst, of the color of Jupiter, but its shape suggests the full moon and the Great Sea of Binah.

In the center is radiant blood; the spiritual life is inferred; light in the darkness."

The Chariot Thoth Tarot

The oracular bottle at the end of Gargantua and Pantagruel is the Holy Grail. As noted, it's trismegistical – thrice greatest – connecting it to Binah, the Great Mother archetype, through key number three.

James Joyce

French writer Valery Labaud called Joyce's novel Ulysses the vastest and most human work written in Europe since Rabelais. (Joyce, Selected Letters). Ulysses shocked and scandalized readers when it came out for its frank portrayal of human bodily functions. Both Joyce and Rabelais examine the human body, its parts and functions, sexual or otherwise in great detail sometimes going deep into its anatomy. Rabelais, after all, was a medical Doctor.

Mythology informed both their works against the ever present background of The Church. Though set in modern times, Joyce modeled Ulysses after The Odyssey, the ancient Greek epic poem by Homer. Similarly, Rabelais has his adventurers sail in unknown lands in the last two books encountering many different unusual, fantastic, inhabitants of strange islands.

The constant wordplay with the aim of packing as many different meanings as possible into any particular word or phrase runs through Gargantua and Pantagruel but is taken several levels beyond by Joyce, particularly in Finnegans Wake. Rabelais experiments with portmanteau words and punning homophones – words or phrases that sound the same but have different meanings: "'By Holy Goosequim!' exclaimed Pantagruel, 'since the last rains came you have developed into a great fill-up-it, Sir – I mean philosopher!'" Later on we have: "'We are lost, all of us. O that now, to kill him, there were here some valiant Perseus.'

'Pursue us: then pierced by me!' Pantagruel replied"

The sounds of the words must be heard to get the puns. Joyce does this so much in Finnegans Wake that it often reads like its own language. Sounding out the words seems the only way to extract some sense from it. This is a form of Cabbala. Cabbala means 'to receive'.

James Joyce

Joyce also inherited Rabelais' penchant for making lists and cataloging things. Both take it to absurdly humorous lengths at times. They both use satire and parody to challenge conventions; they both saw value in learning as many languages as possible. They were both experimental writers. Joyce famously tried different narrative techniques in Ulysses. Rabelais does the same but not to the same extent. Joyce had upwards of three hundred and fifty years more material at his disposal. He had Shakespeare, Jonathon Swift and Laurence Sterne to draw upon. All three show a marked influence by Francois Rabelais.

On the first page, Joyce alludes to the male protagonist of Finnegans Wake, Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker, as a sleeping giant in repose under the landscape of Ireland. The giant theme comes up again on page 6: "And the all gianed in with the shout-most shoviality. Agog and Magog and the round of them agrog." Remember, Joyce uses the sound of words to suggest puns. Therefore, "gianed" suggests gianted; all = Pan; "shoviality" suggests joviality; "shout-most shoviality" implying the physical, slapstick, sometimes cruel humor found in G & P. Agog and Magog connects with a legendary British giant, Gogmagogg, which later got corrupted into two giants, Gog and Magog; "agrog" can refer to an alcoholic beverage recalling the Pantagruelian enthusiasm (agog also = enthusiastic, or excited eagerness) for drinking wine.

Joyce claimed to have not read Rabelais, a little digging proves otherwise. The Joyce scholar John Kidd even tracked down Joyce's copy of Gargantua and Pantagruel which was in the original French. Polyglotism in Rabelais and Finnegans Wake by Jacob Korg is one of many papers looking at approaches and techniques Joyce likely picked up from Pantagruel.

The Nexus of Crowley and Joyce

Both writer/mages borrowed significantly from Rabelais, albeit in different ways. Crowley was very explicit about it, Joyce, more implicit. Did the two know each other's work? We have explicit evidence Crowley read Joyce, he published a review in a magazine calling him a genius. The whole, short review appears in the Nocturnal Revelries blog here. In an excellent biography of Crowley, Perdurabo, by Richard Kaczynski, the author states categorically that Joyce never read Crowley. He doesn't cite how he knows this; my guess is that he made an inference based on a published list of books in Joyce's library that contained nothing penned by Crowley. It sounds disingenuous to suggest that Joyce didn't know of Uncle Al and his philosophy. Both were well acquainted with W.B. Yeats, Crowley even knew Yeats' father. Yeats disapproved of Crowley, but admired Joyce and did what he could to help get him established in the literary world. Later, Yeats invited Joyce to join the Irish Academy. It seems Joyce and Yeats corresponded not infrequently over the years; perhaps the subject of Crowley never came up? Maybe so, but Joyce did read newspapers; Crowley appeared as a subject/target in multiple, salacious newspaper articles particularly in the early 1920s when the alleged scandals of his Abbey of Thelema got splashed all over the tabloids. Those articles included glosses of Thelemic ideology, though highly, unfavorably biased. Circumstantial evidence aside, we find a direct indication Joyce knew Crowley because he clearly invokes him in Finnegans Wake on page 105:

From Abbeygate to Crowalley

Through a Lift in the Lude, Smocks for Their Graces and

Me Aunt for them Clodshopper, How to Pull a Good Horuscoup

even when Oldsire is Dead to the World, ...

A contemporary post-Rabelasian nexus point of James Joyce and Aleister Crowley is found in various books and talks by Robert Anton Wilson. RAW became deeply immersed in both their work and often compared the two, sometimes mashing them together as, for instance, in Masks of the Illuminati.

Robert Anton Wilson

Striking correlations between Rabelais and Robert Anton Wilson are easily noticed. Both endeavored to write a Tale of the Tribe. Both present a didactic, Hermetic transmission couched in humor, satire, parody, and playfulness. Wilson wrote that all his novels and some of his non-fiction books were composed in the Hermetic style; he put a great deal of stock in 'Do what thou wilt'. One clear point of reference in common: the ancient Greek mystic and philosopher, Pythagoras and his school. Pythagoras and different aspects of his system – numerology, geometry, even his dietary habits – turn up frequently in Gargantua and Pantagruel. Wilson outlines a general gloss of Pythagoras in Cosmic Trigger I that sounds very much like his own approach:

"... his work was the first attempt in history to unify science, mathematics, art and mysticism into one comprehensible system and as such is still influential. Leary, Crowley and Buckminster Fuller have all described themselves as modern Pythagoreans."

At one point Wilson became obsessed with Sirius, the Dog Star, going so far as to suspect he might be in telepathic contact with Higher Intelligence coming from there. Pantagruel was born when the Dog Star bays at the Sun – the dog days of July and early August. Like James Joyce and Aleister Crowley, both Rabelais and Wilson appeared to have prophesied future events in their writings.

Robert Anton Wilson

Another tangential connection with Rabelais comes with Wilson's character Frank Dashwood, the head of Orgasm Research in the Schrödinger's Cat trilogy. The character's name comes from the 18th century politician and rake, Sir Francis Dashwood, who is mistakenly said to have started one of the most notorious Hell-Fire clubs that came and went in England and Ireland during that era. The original Hell-Fire club was started a little before Dashwood's time possibly by Philip Wharton, the history is unclear. Members were alleged to be atheist blasphemers who mocked the Church by engaging in Satanic rituals and sexual debauchery; so the story goes, no one really knows exactly what went on. The press conflated Dashwood's equally anarchistic, libertine club, the Monks of Medmenham Abbey, aka the Order of the Friars of St. Francis of Wycombe, with the Hell-Fire Club.

Dashwood is said to have put the one rule of the Abbey of Thélème, 'Do what thou wilt' above the door to his Abbey. It had been a real medieval monastery at one time, founded in the 12th century. Dashwood had it fixed it up and formed a club for the elites of his day entertaining notables like Benjamin Franklin and many prominent British politicians. During the restoration of Medmenham, workers found an old Madonna statue. Dashwood had it spruced up and placed front and center in the courtyard. RAW calls Medmenham Abbey, the "Abbey of St. Francis" in his historical novel, The Widow's Son but notes that the press more accurately called it "the Hell Fire Club – a kind of society of freethinkers and atheists who took perverse pleasure in burlesquing the sacraments of Christianity." He then references a possibly apocryphal story concerning the Earl of Sandwich getting bitten by an orangutan during a Black Mass there. Skeptics suggest that it was really the local Anglican Bishop dressed up in an orangutan suit.

Last, but not least: Rabelais writes a long list of useless and preposterous activities of one outrageous character where it is said: "if he dreamt: it was of flying phalluses scrambling up walls." A flying phallus serves as a recurring motif in Schrödinger's Cat.

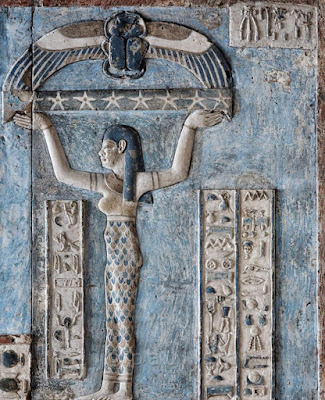

Introducing Ms. God – the Divine Feminine

More common ground (or sky) shared by James Joyce and Aleister Crowley involves placing the archetype of the Great Mother centerstage in their works. Joyce does so with the character Anna Livia Plurabelle in Finnegans Wake; before that, with a perspective from deep inside a woman's consciousness – Molly Bloom in Ulysses. After reading the latter, renowned psychoanalyst and hermetic philosopher Carl Jung quipped: "only the devil's grandmother knows so much about the real psychology of a woman. I didn't." Crowley's sacred text, The Book of the Law, begins with "[t]he manifestation of Nuit." Nuit originates from the ancient Egyptian sky goddess, Crowley promotes her to a star Goddess. She represents the Divine Feminine at its most expansive and all encompassing, among many other things. She invites humanity to join her:

Now, therefore, I am known to ye by my name Nuit . . . Since I am Infinite Space, and the Infinite Stars thereof, do ye also thus. - Al:I:22

Relief of Nuit from the Dendera Temple, Egypt

Crowley's gig centered upon announcing the aeon of Horus. He said the formula of this aeon is the tarot card, The Chariot. The charioteer is built into the chariot. "His only function is to bear the Holy Grail." The Holy Grail carries the pure essence of the Divine Feminine.

Joyce seems to have understood this about Crowley, while also pointing to another source for introducing the feminine into contemporary spirituality, Francois Rabelais. I infer this because the above quote from Finnegans Wake that alludes to both Rabelais and Crowley appears in the section that introduces Anna Livia Plurabelle. This glorious, Nuit-like introduction is worth quoting:

In the name of Annah the Allmaziful, the Everliving, the Bringer of Plurabilities, haloed be her eve, her singtime sung, her rill be run, unhemmed as it is uneven!

Her untitled mamafesta memorialising the Mosthighest has gone by many names at disjointed times.

The last line seems one of Joyce's paradoxes or jokes because although this mamafesta (manifesto/mama festival/mama feast) may be untitled, its many names (which aren't titles apparently) goes on for about three pages. One of those names is the above quote that starts: "From Abbeygate to Crowalley . . ."

I contend that Rabelais was an early disseminator for introducing the sacred feminine principle into Western thought. Let's begin in the middle of Gargantua and Pantagruel then make our way forward and backward to each end. We'll start with the Joyce reference – Abbeygate. It's been incorrectly stated that the words 'Do what thou wilt' were inscribed over the entrance gate to the Abbey of Thélème. 'Do what thou wilt' was the only rule of the Abbey. The inscription over the gate goes on for about three pages and describes the kind of people welcome to come inside and those who are not. Nothing is said about gender until the penultimate stanza:

Enter herein you dames of good descent,

Come with frank minds and with us find true joy:

Beauteous Flowers, with faces Heaven-bent,

Upright and pure, on Wisdom all intent;

In the notes preceding the second chapter of Book 1, "On the Nativity of the Most-Redoubtable Pantagruel," M. A. Screech informs us that along with the landscape of the Old Testament, the story is also set in a comic version of Thomas More's Utopia which had been out for less than twenty years at that point and only available to Latin readers. Pantagruel's mother, Badebec, was the daughter of the King of Amaurotes in Utopia. Unfortunately, Badebec dies giving birth to Pantagruel. Gargantua is torn between weeping for the loss of his wife or laughing for joy at the birth of his son. This dialectic between the highest and the lowest, or between comedy and tragedy informs the whole book.

I postulate that Pantagruel's mother dying upon childbirth provides a metaphor for the death of the role of Female intelligence in the birth of The Church. In the Fourth Book, Rabelais makes the Greek god Pan correspond with Christ; Pantagruel's birth thus alludes to the birth of Christ and the resulting establishment of the Church without the Mother. Gargantua's loss echoes the world's loss:

'Should I weep?' he asked. 'Yes, Why? Because my good wife is dead, who was the best this and the best that in all the world . . . Her loss to me is immeasurable. O God of mine! What have I done that you should punish me so? Why didn't you send death to me rather than her? To live without her is for me but to languish. . . Alas, my poor Pantagruel: you have lost a good mother, your gentle nurse, your most beloved lady! Ha, false Death, how malevolent, how cruel you are, to take from me her who, as of right, deserves immortality.' (emphasis added)

Rabelais certainly didn't appear to be a feminist, none of his principle characters are women. He also seems no misogynist.

Pantagruel takes Panurge to various oracles attempting to divine the answer to the latter's matrimonial question. Pantagruel explains how each oracle works. At the oracle of dream interpretation he says: the soul often foresees what is to come, and then goes on to explain. Quite out of the norm for his time, Rabelais represents the soul as female. In that era, following Plato, the soul was thought to be genderless. As the body sleeps, she – the Soul – is able to go back to her home in Heaven:

From there, she is granted the signal favor of participating in her primal and divine origin and of contemplating that infinite Sphere whose center is in every place in the universe and whose circumference nowhere: God, that is, by the teachings of Hermes Trismegistus in whom there is no becoming, no transience, no waning, all times being the present; there she discerns things not only past amongst the motions here below but also things to come; she bears them back to her body, and as she expounds them to her friends via her body's organs and senses she is termed prophetic . . .

Many years later, this found its way into Crowley's Book of the Law: "In the sphere I am everywhere the center, as she, the circumference, is nowhere found." - Al:2:3. Crowley conceives this sphere as the union of the archetypal male – Had, the center – with the archetypal female – Nuit, the circumference. Qabalists will note that this appears as the 3rd verse (key 3 = Binah – the Mother) in the 2nd chapter (key 2 = Chokmah the Father).

To reiterate, Cabbala runs throughout this epic adventure. Therefore, it corresponds quite nicely that Rabelais dedicated the Third Book to Marguerite, Queen of Navarre. He had to receive permission to do this, probably from her brother, Francois I King of France. Marguerite became Queen of Navarre through marriage. She had become a patron and protector of Rabelais. She also wrote books; Screech describes her as liberal, platonizing, defender of evangelicals – some frowned upon by her royal brother – and attracted to the mystical teachings of Hermes Trismegistus. Rabelais begins Book 3 with the short dedication:

FRANCOIS RABELAIS

to the Mind

of the

Queen of Navarre

Abstracted Mind, enraptured, true ecstatic,

Who Heaven dost frequent whence thou derivest

(Leaving behind thy host and place domestic,

Harmonious body, which in concord striveth

To heed thine edicts: stranger, it arriveth

Bereft of senses, calm in Apathy)

Deignest thou not to make a lively sortie

From thine abode divine, perpetual,

This Third Book here with thine own eyes to see

Of the joyful deeds of good Pantagruel?

A direct call to the Divine Feminine comes at the end of chapter 53 of the Fourth Book with a pun:

"Deacon!" said Homenaz "Deacon! Beacon! Shine light over here with double lanterns. And girls: bring in the fruit . . . O, good my God, whom I adore yet have never seen, open for us, by special grace – at least in the article of death – the most sacred treasure of Holy Church, our Mother, of which thou art the Protector, Guardian, Custodian, Administrator and Distributor . . ."

When Pantagruel and Panurge receive the advice to seek the oracle of La Dive Bouteille, the plot essentially becomes a quest for the Holy Grail with a variety of situations and adventures along the way, Once on the island, to get to the Holy Grail, they must make the archetypal journey through the Underworld. Their guide is the High Priestess Bacbuc. Note the similarity between her name and Pantagruel's mother, Badebec. William Tindall points out that James Joyce coins the word "baccbuccus" (Finnegans Wake, p. 116) which combines Bacbuc with Bacchus, the Roman god of wine and pleasure who also shows up toward the end of the Fifth Book. Baqbuq is the Hebrew word for flask.

Frank Zappa benefited greatly by by putting one iteration of the Holy Grail, a strong female presence, front and center in his music. One day in the early 80s, Moon Zappa wrote a playful note to her father suggesting they work together on a song so she could spend more time with him. Frank took her up on it and came up with "Valley Girl" featuring 14 year old Moon ad libbing different scenarios in "valley-speak" caricaturing the San Fernando Valley youth culture where she went to school. The song, continuing the long tradition of social satire dating back to Rabelais, took on a life of its own spawning a Valley Girl cottage industry successful to this day. It was also Frank Zappa's only successful commercial hit song and brought in much extra revenue that allowed him to pursue other artistic interests like his experimental orchestral music.

Pantagruelion

Pantagruelion is a plant spoken of with great enthusiasm. It has "so many virtues, so many powers, such perfection and so many wonderful effects." It's basically a cannabis plant so many people believe it concerns the joys of ingesting THC and getting high. However, on the surface at least, the reference is to hemp. Great detail goes into all the things that can be done with hemp which one commentator believes is a metaphor about industriousness in the world. Rabelais specifically says that the female plant, what provides strong THC, "serves no useful purpose." This may or may not be a dodge; I see no indication of a hidden agenda about getting high. He does go into the anti-inflammatory properties made possible by boiling the root and ingesting it, what we now know as CBD, which is derived from the male plant. The male plant only contains trace amounts of THC. The only clue he may be referring to pantagruelion as consciousness altering comes with the ambiguous statement: "By exploiting the virtues of this plant, Pantagruel has put new and painful thoughts into our minds, worse than those stirred by those giant Aloïde." Rabelais then speculates that perhaps the children of Pantagruel will discover another plant with similar powers which will allow humanity to visit the stars. It's easy to think of this plant as psychotropic.

Laughter is the Best Medicine

Rabelais, ever the Cabbalist and Medical Doctor, begins Book 3 with an address to his patron about why he wrote this book:

Most-illustrious Prince: you have already been duly informed how I have been daily solicited, begged and importuned by so many great personages for the sequel to my pantagruelic mythologies, of the grounds that many of the ailing, the sick, the weary or the afflicted have, when they were read to them, beguiled their benighted sufferings, passed their time merrily and found fresh joy and consolation. To whom I normally reply that, as I wrote them for fun, I sought neither glory nor praise of any kind: my concern and intention were simply to provide such little relief as I could to the absent sick-and-suffering as I willingly provide to those who are present with me, seeking help from Art and my care. Occasionally I explain to them at some length how Hippocrates (describing in several places especially in the Sixth Book of the Epidemics, the formation of his doctor-disciple). . .

He frames the whole purpose of his comedy writing in terms of the best way for a doctor to provide for a patient. To illustrate the multiple sides of his writing, he uses the parable of the Emperor's daughter Julia appearing in provocative dress before her displeasing father Octavian Augustus. The next day she's dressed chastely and her father says, that's more like it. She explains that today I dress for the eyes of my father, yesterday for the eyes of my husband. Rabelais compares his writing to a female voice dressing differently, wearing different masks for different occasions. He brings up the Sixth Book of the Epidemics by Hippocrates again for the belief mentioned therein that the doctor's demeanor or "vibe" determines the outcome of the patient's health to a significant degree. He raises the question of whether the patient's health improves or worsens by contemplating the happy or gloomy qualities of the doctor or whether it's due to "the pouring of the doctor's spirits, serene or gloomy, aerial or terrestrial, joyous or melancholic, from the doctor into the person of his patient (as in the opinion of Plato and Averroës) . . . "

It boils down to: everything must aim at one target and tend towards one end, namely to cheer him up without offence to God and never to depress him in any manner whatsoever.

The second option, 'the pouring of the doctor's spirits', sounds like what Sufis call the transfer of baraka. Remember, this metaphor of the doctor/patient relationship gives the rationale of why he wrote Pantagruel. Rabelais is the doctor, the patient is the world. On the following page, he finds a way to cite the Sixth Book of the Epidemics for a third time (666). Of course, the metaphor of literature as a doctor fits very nicely with Gilles Deleuze's notion that literature functions as a cultural diagnostic tool.

Rabelais' philosophy came to be known as pantagruelism loosely defined by M.A. Screech as "a smiling, charitable and tolerant wisdom which accepts and surmounts misfortune." It has this in common with the Stoics. Pantagruelism might be thought of as a pragmatic approach to Stoic philosophy. Rabelais clarifies a bit more in Book 3:

"I will recognize in all of them a specific form and an individual property which our elders called pantagruelism, by means of which they will never take in bad part anything they know to flow from a good, frank and loyal heart. I have regularly seen them accept good-will as payment and, when attributable to weak resources, be satisfied with it."

Compare this with the metaphor above of a doctor pouring their spirits onto the patient.

Sainte Chapelle

I have commented frequently in the past on the cabbalistic SC letter combination found quite a bit in the literature of Robert Anton Wilson, Thomas Pynchon, Aleister Crowley with additional appearances in James Joyce and Gilles Deleuze. It seems to have something to do with food, particularly divine food known as manna. For example, by Gematria, S + C = 68 (Samekh + Cheth). Crowley's cabbalistically numbered Book of Lies chapter 68 has the title "Manna." Elaboration upon the basis of this motif can be found in Thelema, Deleuze and 68. Some examples appearing in Robert Anton Wilson's oeuvre can be seen in this post on Gematria. I have often wondered where this semiotic coding originated? Perhaps in The Third Book of Pantagruel:

"'I know what you mean!' Frère Jean replied. 'That metaphor has been served up from the cloister cooking-pot . . . For in my days, whenever the monastic fathers got up for their mattins (morning prayers), they, following a certain ancient practice – cabbalistic: not written but passed down from hand to hand – performed certain noteworthy preliminaries before going into church: they shat in their shitteries, pissed in their pisseries, spat in the spitteries, melodiously hacked in the hackeries and raved in the raveries, so as to bring nothing impure into divine service. Which done, they would devoutly proceed to the Saint Chapelle (for that was the name for the monastery's kitchen in their enigmatic jargon) and there devoutly urge that the beef for the breakfast of Our Lord's monastic brethren be put then and there on the fire.

Often they lit the fire under the pot themselves.

I repeat: "Often they lit the fire under the pot themselves."

The real Sainte Chapelle in Paris

Traveling through the Underworld on their way to the oracle of the bottle, the High Priestess Bacbuc takes our heroes to a Temple at the center of which is a most marvelous fountain. The waters of this fountain taste like whatever wine the drinkers choose. After quenching their thirst, Bacbuc asks them what they think. Unsatisfied with their answers, she determines that their palates need cleaning:

And so there were brought in lovely, fat, happy hams, lovely, fat, happy smoked ox-tongues, lovely tasty, salted meats . . . and other such chimney-sweepers of the gullet. At her command we ate until we had to admit that our stomachs had been well and truly scoured clean by a thirst which had quite dreadfully plagued us.

Bacbuc then improvises on the story of Moses providing manna from Heaven when the Israelites were wandering in the desert, as told in Exodus. Only this manna, as Bacbuc tells it, similar to the waters of the fountain, tastes like whatever food you want. She takes them back to the fountain: "Bring your mind to it and drink!"

The waters of the fountain seem to have a life-giving quality to them. The fountain's form, as described, seems prophetic of a life replicating molecule discovered in the 19th century and decoded by Science in the 20th century.

"The outflowing water gushed from that fountain through three pipes and channels made of fine pearls and sited at the apex of three equilateral angles at the tip of the fountain as described above. Those channels projected in the shape of a double helix."

The big discovery/decoding of the life transmitting DNA molecule is its double helix structure. This begat the new science of molecular biology. The monumental importance of this to human progress doesn't need to be said and is yet to be fully known; you could call it a giant discovery. I don't know if these Sherlock Homes-like, scientific sleuths, James Watson and Francis Crick, the double helix DNA model formulators, were pantagruelions, but they tapped into something.

Bacbuc, the High Priestess, explains how the double helix form affects the fountain's water:

" . . . it is entirely via the form of that twin spiral which you can see, together with that five-fold fleuron (flower shaped) which vibrates with each internal impulse – as in the case of the vena cava where it enters the right ventricle of the heart – that the waters of this holy fountain filter out, producing a harmony such that it rises to the surface of the sea in your world."

Conclusion

Writing at a time when expressing the wrong thing could easily get you killed or locked up, Rabelais managed to engage in a very broad range of social, political, and ecclesiastical satire and have his audience, including the Establishment, clamoring for more. He took his humor-laced criticism right to the edge and reeled it back. The edition I have shows the revisions he made from the first edition in 1532 to the second, definitive edition published in 1542. He expanded many of the passages, but also changed things, adding ambiguity, to avoid upsetting certain Authorities when the satire got a little too direct.

Rabelais always operates within the mystical dimension of Christianity. He brings in pagan and hermetic wisdom to expand the Judeo-Christian framework from within. For instance, calling KNOW THYSELF (caps in the book) the "Law of Moses" given to the Jews. The very next sentence explains that this law appeared on the temple of Apollo at Delphi. Rabelais seems receptive to the wisdom and understanding at the core of all doctrines. Like Crowley, he selectively quotes many passages from the Bible to support his points. Other times, he'll modify Biblical phrases in his narrative to suit his purposes. He identifies Pan with Christ.

His mentor, Erasmus, expressed this blending well:

Sacred scripture is of course the basic authority for everything; yet I sometimes run across ancient sayings or pagan writings – even the poets – so purely and reverently and admirably expressed that I can't help believing that the author's hearts were moved by some divine power. And perhaps the spirit of Christ is more widespread than we understand, and the company of the saints includes many not on our calendar.

Like many of the works it would later inspire, Gargantua and Pantagruel communicates on many levels simultaneously. It can be read for sheer fun and entertainment; a burlesque carnival approach to this adventure we call life. The fart jokes alone are worth the price of admission. It can be read as a compendium of folktales dispensing the common sense and morals of the day; or as scathing satire on established Institutions couched in humor. Monty Python and Frank Zappa are just two of the many artists who carried on that tradition. Many comedians as well: Lenny Bruce, George Carlin, Richard Pryor and Eddie Izzard to name just a few. Influenced by Thomas More's Utopia, Rabelais expresses a hopeful vision for humanity with an inherent hidden agenda that things can get better. Also hidden, how to go about putting this vision into action.

Receiving the full Hermetic transmission seems incumbent on getting initiated into its mysteries. It appears axiomatic in the Western occult tradition that the only real Initiation is self-Initiation. The transmission is hermetically sealed but it can be unlocked. It presents a challenge for the reader who is also interested in the Great Work of transformation.

I'll end with a quote that exemplifies the inclusion of Hermetic philosophy – the infamous "as above, so below; as below so above" relationship of the microcosm (the individual WoMan) with the macrocosm (Universe) – into Christian symbolism. It also illustrates what G. I. Gurdjieff called "the Law of Reciprocal Maintenance." Lastly, it says in different words Gilles Deluze's statement that sense must be produced.

"For Nature created Man but to lend and to borrow. The harmony of the heavens will not be grander than the harmony of his polity (community).

The intention of the Founder of this microcosm is to maintain therein its soul, whom he has placed within as its host, its life. Now life consists in blood. Blood is the seat of the soul. That is why one single task weighs down upon this microcosm: continually to forge blood. And in that forging all its members are in their proper roles, their hierarchy being such that each borrows from the other, each lends to the other. The material – the substance – proper to be transmuted into blood is supplied by Nature: bread and wine. Within these two are comprehended every kind of food . . ."

Or as The Beatles put it: I get by with a little help from my friends.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)