"Of the sleep of Ulro! and of the passage through

Eternal Death! and of the awaking to Eternal Life

This theme calls me in sleep night after night & ev'ry morn

Awakes me at sun-rise, then I see the Saviour over me

Spreading his beams of love, & dictating the words of this mild song.

Awake! awake O sleeper of the land of shadows, wake! expand!

I am in you and you in me, mutual in love divine: . . ."

- Opening lines to Jerusalem by William Blake

"William Blake's Jerusalem should be added to the list of major sources for James Joyce's Finnegans Wake" – Karl Kiralis

In the previous episode, I postulated that Joyce used Finnegans Wake to show HOW to construct something. It began with the premise that Howth Castle and Environs (HCE) signified an alchemical pun. That something = the construction of stable and permanent structures of higher consciousness; higher bodies in a largely unknown new territory. Put another way: awakening and accessing, at will, higher brain circuits. Why would anyone even bother? Of what use is it to explore and map out unknown territory? Why would Joyce encode instructions for a metaphysical construction in his monumental undertaking to explore the Night?

In Plato's dialogue, Phaedo, an account occurring on Socrates' last day alive, Socrates says that "true philosophers ... are always occupied in the practice of dying." In The Consciousness of Joyce, Richard Ellman notes that Joyce possessed a copy of Phaedo. The practice of death concerns the separation and release of the soul from the body. According to Socrates, true philosophers are "ever seeking to release the soul," it is their "especial study." Therefore philosophers are "ever studying to live as nearly as they can in a state of death."

Let's update the terminology with Timothy Leary's 8 Circuit model of consciousness: the four lower "terrestrial" circuits represent the "body" and the four higher "extraterrestrial" circuits represent the "soul." The practice of dying, or as Sufis put it, dying before you die, consists of temporarily moving (separating) one's primary attention and awareness from the terrestrial circuits to the extraterrestrial circuits, from the body to the soul. We'll call the source of awareness and attention concerned with the physical body, emotions and intellect of the terrestrial circuits, the ego or personality. The terrestrial circuits and their operation are also known as the human biological machine since they function largely mechanically. The source of attention still remaining after the ego temporarily disappears, i.e. the "soul," we'll call the "voyager" as the environment (territory) it passes through constantly changes and shifts as if on a journey or voyage.

In this reading, Howth Castle = how to construct a stable structure; Environs designates the territory of the higher dimensions – the territory of death from the point of view of the ego; commodius vicus of recirculation might indicate the practice of philosophy as Socrates saw it, the constant practice of dying.

The construction of a stable, crystalized body of consciousness able to hang out in the higher dimensions not only serves to enable the practice of dying, (separating the soul from the body) it also desires to survive the death of the biological form, the physical body. The territory and environs of the higher brain circuits appears largely, if not completely, unknown to the ego and personality that directs the activities and functioning of the body. If one doesn't practice death before dying, by raising consciousness, this territory can come as an overwhelming, even terrifying shock to the voyager when the ego disappears at discorporation. It's my premise here that Joyce incorporates within the Wake various strategies for surviving Death.

Many Joycean scholars and enthusiasts see Finnegans Wake as a journey through the Night. This book speaks a specialized and very complex dream language causing some to interpret the whole thing as the dream of Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker, the central character. Mythologically, it can also represent the dream of Finn MacCool, the legendary Irish hero whose giant form rests across the landscape of Ireland lying in a perpetual trance (bardo) in lieu of death.

Finnegans Wake and the territory of Death share a labyrinthine quality in common; a maze-like complexity often baffling and disorientating. It's easy to get lost in either. Multiple cultures have devised various strategies, spells, disciplines, codes and instructions for navigating the Land of the Dead. The two most well known examples being the Bardo Thodol, more commonly known as the Tibetan Book of the Dead, and the collection of spells entombed with the deceased in ancient Egypt called the Papyrus of Ani, aka The Egyptian Book of the Dead. The latter appears explicitly multiple times in the Wake.

The journey the soul embarks upon following the dissolution of the physical body is said to be fraught with great peril and danger; with overwhelming lights, sounds, sensations and radiations. It could be compared with a robust psychedelic trip encountering intensely strange and disorientating territory following the temporary death of the ego. The instructions, spells and advice found in Books of the Dead intends to help guide the voyager through the daunting labyrinth between death and rebirth. In its role as a Book of the Dead, Finnegans Wake guides the reader through this unnerving landscape. One way it does this is by presenting a very difficult, but solvable maze to unravel. Learning to solve one maze – to become maze bright – strengthens skills for solving other mazes like that of the afterlife.

All the mythologies concerned with the technology of Death include rebirth or resurrection. The instructions found in such Books are also meant to help the voyager select a either a favorable rebirth or transcend to a level beyond the human cycle of death and rebirth. We don't have a word in the English language to signify the territory between death and rebirth so we'll appropriate the Tibetan word for it, the Bardo.

Every night when we go to sleep our waking consciousness experiences a little death then gets reborn in the morning to a new day. The world of dreams appears conterminous with the Bardo; the unraveling of the conscious mind is common to both situations. Joyce's Book of the Night therefore becomes a Book of the Dead. "James Joyce once suggested to his friend Frank Budgen that he should compose an article on Finnegans Wake and title it James Joyce's Book of the Dead." *

~

*quoted from Joseph Campbell, Mythic Worlds, Modern Words. His source is an article by Frank Budgen, "Joyce's Chapters of Going Forth by Day," in Horizon, 1941

~

On Wake pages 30 and 31 Joyce writes of the genesis of his protagonist's name, Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker. In Mythic Worlds, Modern Words, Campbell interprets this passage as deriving Earwicker from "earwig ("ear-beetle"). He continues: "This 'dangerous' insect is Joyce's Irish counterpart and parody of the scarabareus (the Mediterranean 'dung beetle') which in Egyptian iconography represents Kephra, the sun-god, and is a primary symbol of resurrection and immortality. . . . Earwicker ('Awaker'): he is the earwig in the sleeper's (i.e. reader's) ear. And Finnegans Wake itself is the accompanying papyrus, The Book of the Dead." (Mythic Worlds footnote p. 299).

Campbell made this point earlier in his book:

"Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker: An earwig is a bug that gets in your ear and keeps buzzing. This can be compared to the Egyptian scarab, which is put on the heart of a person being buried in a sarcophagus and represents the reawakened. 'Earwicker' can be read as the awaker and the word Buddah means 'the one who is awake.'" (p. 242)

Waking up in the Buddhist, Hindu, or Sufi sense - waking up from the world illusion or the life dream – seems exactly what happens to the voyager when the body dies. Learning how to "wake up" appears another practice of dying before you die.

In Joyce's Book of the Dark, John Bishop writes:

"There are several good reasons for approaching Finnegans Wake, and it's treatment of the wake, through a reading of the Book of the Dead. Joyce actively sought to have someone write an essay exploring the Wake's affinities with this text; as he explained in a letter to Harriet Shaw Weaver, one of the '4 long essays ' in his testamentary collection which he planned to have follow "Our Exagmination" was to examine specifically the Wake's reconstruction of the night in reference to the Book of the Dead."

Joseph Campbell sees Khephra as one identity of Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker (HCE). Khephra is a big deal in the Thelemic pantheon. He is the ancient Egyptian God associated with the scarab who represents the Sun at midnight. Kephera carries the Sun through night to its rebirth in the morning just as HCE carries the reader of Finnegans Wake through the Night to rebirth in a new day. Another name for the Egyptian Book of the Dead is the Book of Coming Forth by Day. The name Khephra means to "come into being" or "becoming."

In the Thelemic rituals of "The Mass of the Phoenix" (Chapter 44 in the Book of Lies) and "The Great Invocation" (Magick Book 4 p. 672 Weiser, 1994 first edition) Khephra is identified as an aspect of Horus, the crowned and conquering child who presides over the new Aeon; it's implied in the former and explicit in the latter. Both those rituals serve to invoke Horus, meaning that the practitioner completely identifies themself with the god for the duration of the ritual. For example we have from the latter:

Hail, O An-Kert (goddess of fertility), who hidest thy companion in the womb!

Hail, Khephra, self-created!

Grant that the dead man Ankh-f-n-khonsu may come forth with victory to behold the Disk, and that he may journey forth to see the Great and Inscrutable God, who dwelleth in the Infinite. . . .

Yet my form is the form of Khephra: my locks flow down as the locks of the earth before Tum, the locks of earth before Tum! (Magick, p. 674 - 675)

Tum represents the Sun at dusk making this Khephra entering into the Night.

Both Crowley and Joyce draw heavily and directly from the Egyptian Book of the Dead and both found at least some of this Egyptian inspiration from the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. However, Finnegans Wake functions as a Book of the Dead far beyond its specific allusions to the Papyrus of Ani; in the Wake's dream language, the Papyrus of Anna – Anna Livia Plurabelle.

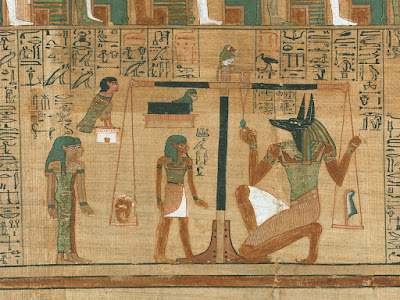

Scene of the weighing of the heart from the Egyptian Book of the Dead

* * * * * *

The touchstone tale for descent and journey through the Underworld is Dante's The Divine Comedy consisting of three books: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. In Mythic Worlds, Modern Words Joseph Campbell presents the theory that Joyce modeled his oeuvre, beginning with The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, after the literary works of Dante Alighieri. Portrait, he says, parallels Dante's first work, a collection of poems and commentary dedicated to his muse, Beatrice Portinari. Campbell explains that Ulysses corresponds with Inferno and Finnegans Wake with Purgatorio – Purgatory. Paradiso was to be Joyce's next book. He didn't have the opportunity to write it before exiting his mortal coil. Joe doesn't fully explain the Purgatorio – Wake correspondence, but we find evidence for it beginning with18 references in Finnegans Wake to a small cave called St. Patrick's Purgatory on an Irish island where legend has it that St. Patrick found the entrance to Purgatory. These begin on page 80: "her filthdump near Serpentine in Phoenix Park (at her time called Finewell's Keepsacre but later tautaubapptossed Pat's Purge)" . . .

The word Purgatory means "cleansing" – purging; "her filthdump." These references recur until nearly the end of the book: "Reparatrices for a good allround sympowdhericks purge, full view . . . " (p. 618).

Purgatory describes a Bardo space as it's in between Hell and Heaven just as the Bardo lies in between Death and Rebirth. One definition of the Bardo: any space that's in between or in transition. Campbell says that Joyce makes an analogy between purgatory and reincarnation. "What is being reincarnated is not only the individual, but also the universe." (MWMW p. 20).

Purgatory may have its genesis in Egyptian mythology. In The Gods of the Egyptians (Vol. I p. 171), E.A. Wallis Budge surmises that Purgatory has its roots in their notion of the Tuat, a valley which separated this world from heaven. Like the purgatory of Finnegans Wake, a river runs through the Tuat said to be a counterpart of the earthly and the celestial Nile. Cleansing appears a big part of what occurs in the Bardo with the voyager confronting all their subconscious "monsters and demons" (impurities and regrets) in order to recognize them as aspects of their own consciousness and let them go; purge them.

* * * * * *

Let's examine a paragraph from p. 593 that has multiple sources with Bardo imagery: an Egyptian Book of Coming Forth by Day influence, a Biblical reference, an alchemical allusion, and a cabalistic communication. It's the 4th paragraph in the fourth and final section. In this part of our beloved story, night has ended and a new day is dawning by calling Array! Surrection! – a ray of sunlight coming through and a resurrection. A half page later:

The eversower seeds of light to the cowld owld sowls that are in the domnatory of Defmut after the night of the carrying of the word of Nuahs and the night of making Mehs to cuddle up in a coddlepot, Pu Nuseht, lord of risings in the yonderworld of Ntamplin, toph triumphant, speakth.

Much to unravel here. Buckle up your seat belts, folks! Nuahs and Mehs are Shaun and Shem reversed, these are the names of the twin sons of HCE. Shaun is a postman, carrying the word – communicating. Shem is a penman, a writer who creates with words. Coddlepot suggests a cobblepot, a hastily assembled pot, container, or vessel. To "cuddle up in a cobblepot" could indicate embracing "up" (up = higher consciousness) through cobbling up a vessel – a higher body of consciousness.

Joyce reverses names to multiply linguistic sense. For instance, Nuahs appears a conflation of the Egyptian goddess Nu and Noah of Biblical fame. Carrying the word of Nuahs = the mission of Noah's Ark. The "cowld owld sowls" (cold old souls) represent the animals a cow, owl and sow. The "domnatory of Defmut" reminds me of purgatory if you take it as damnatory of silence; Defmut = deaf mute = silence. These souls/animals are in the domnatory, the ark, with the night symbolizing the Great Flood. The story of Noah's Ark is another tale of traveling through death (of all life on Earth except for those in the Ark) to the resurrection of a new beginning.

It's been established by multiple scholars that James Joyce was a master of Cabala. The aspect of Cabala called Notarikon considers the significance of the initials of words. The letter N, as in Nuahs, corresponds with the card of Death in the Tarot. Thus, "the night of the carrying of the word of Nuahs" cabalisticly gives us "carrying the word of Death," i.e. a Book of the Dead.

The M of Mehs corresponds with the Hanged Man card. Consulting the description of it in Crowley's The Book of Thoth shows its relevance to themes here. I advise reading the whole description but here are some relevant quotes: "This card, attributed to the letter Mem, represents the element of Water. It would perhaps be better to say that it represents the spiritual function of water in the economy of initiation; it is a baptism which is also a death." A serpent appears around the left foot of the Hanged Man. "In this inferior darkness of death, the serpent of new life begins to stir. " If we interpret "domnatory" as a portmanteau of dominant and territory then "domnatory of Defmut" becomes the dominant territory of silence. Returning to The Book of Thoth: "and the sound M (is) the return to Eternal Silence, as in the word AUM. . . . Through his Work a Child is begotten, ("cuddle up in a coddlepot" displays child-like language) as shown by the Serpent stirring in the Darkness of the Abyss below him. . . . Moreover, Water is peculiarly the Mother Letter . . . in Nature, Homo Sapiens is a marine mammal, and our intra-uterine existence is passed in the Amniotic Fluid. The legend of Noah, the Ark and the Flood, is no more than a hieratic presentation of the facts of life,"

The Wake quote from p. 593 certainly has an Egyptian Book of the Dead feel to it. Some say that Defmut alludes to the Egyptian goddess Tefnut which fits the Noah's Ark narrative as she is the goddess of rain. Defmut could also allude to Duatmutef, one of the sons of Horus who also corresponds to Mem (Water; Hanged Man) in a table found in Magick, p. 540.

"Pu Nuseht" though it sounds Egyptian, seems nothing more than "The sun up" reversed. However, the reversed "up,"a separate word here, could serve to qualify and link to the "up" of "cuddle up", i.e. cuddle up to the sun. I learned from Peter Quadrino's excellent blog,

Finnegans, Wake! that

"Ntamplin" is a quasi Greek way of spelling Dublin (he explicates the whole passage in greater detail

here.) Since the Bardo, in one sense, seems an unraveling of the subconscious mind, Dublin undeniably factors into the Bardo ("the yonderworld" – underworld) of James Joyce; "toph (top) triumphant" connects with the direction of "up". Quadrino and others point out that "toph" gets close to an anagram for "photo " the Greek word for light, but it's also close to an anagram for Ptah, an older solar god from Memphis, Egypt who is considered the personification of the rising sun – fitting in with the new day theme here.

The

"eversower seeds of light" (the Sun?) speaks. An excellent analysis of what it says is given in the

Finnegans, Wake! blog

here. For our purposes, I'll note the sentence:

"Verb umprincipiant through the trancitive spaces." Transit is another term for being in the Bardo (transitioning); trancitive spaces suggests bardo spaces. Being in a trance describes another kind of bardo space. Principiant comes from the Latin principiare - to begin. The "Um" is a mostly obsolete prefix for "about" therefore

umprincipiant could mean "about to begin. "Verb" = voyager cf. Buckminster Fuller's famous quote, "I seem to be a verb" which he also used as a title for a book. We end up with the Voyager going through bardo spaces awaiting rebirth or resurrection – about to begin.

Before we move on, it should be noted that the Noah's Ark reference appears more than simply another resurrection story. The notion of an Ark, a fortified vessel carrying pressure cargo through the "dark and stormy night" or whatever metaphor you choose for difficult times, appears an important, recurring theme in the Wake as a Book of the Dead. In this dream language,, a homonym for Ark, "arc", as in a shaft of life arcing through the darkness, communicates the same theme of carrying light through the night; this also describes Kephra's (HCE) function.

The last sentence of the second paragraph in the Wake (p. 3) connects with the quote we've been looking at from p. 593:

"Rot a peck of pa's malt had Jhem or Shen brewed by arclight and rory end to the regginbrow ringsome on the aquaface."

HCE's sons, Shem (Jhem) and Shaun (Shen) appear in both quotes, their names spelled forward here. We find an explicit allusion to the arc (arclight) – Ark homonyms. Then, "regginbrow ringsome on the aquaface" obviously refers to the rainbow, God's promise to Noah, that appeared after the rains had subsided and the world was covered in water ("aquaface").

* * * * * *

I am more interested in parallels between the material presented in Finnegans Wake with the philosophy of Thelema than to any mention or allusion to the human being Aleister Crowley. The "eversower seeds of light" phrase from p. 593, though metaphorically consonant with the rising of the sun, suggests some kind of personification of the sun. We find such a personification in the form of the Egyptian god Khem.

"Khem (is) an ithyphallic deity . . . generally represented as standing upright, with his arm extended in the act of scattering seed. . . Khem represented the idea of divinity in its double character of father and son. As father he was called the husband of his mother, while as a son he was assimilated to the god Horus. He symbolized generative power surviving death." (Rawlinson, History of Ancient Egypt)

The central altar piece in Thelema is known as The Stele of Revealing. It was the funerary stele (tablet) of the priest Ankh af na Khonsu who lived circa 6th Century B.C. Khonsu was a priest of Menthu, a local Sun-god, in Thebes. Crowley considers Menthu an iteration of Horus for having the head of a hawk. In the Thelemic cosmogony, Horus represents the deity reigning over the new Aeon which began in 1904 with the reception of The Book of the Law. In at least three important Thelemic rituals, "The Mass of the Phoenix", "The Great Invocation" and "Liber Samekh", the aspirant identifies themself with the dead man Ankh af na Khonsu traveling through the underworld to get reborn as Horus. "The Great Invocation", in particular, borrows heavily from the Egyptian Book of the Dead. This is where Khem, the "eversower seeds of light" comes in.

In Section Aa of "Liber Samekh", a ritual for invoking the Holy Guardian Angel – in one sense, a person's deepest and most true Self, the True Will – we see:

I am ANKH-F-N-KHONSU Thy prophet, unto whom Thou didst commit Thy Mysteries, the Ceremonies of KHEM . . .

Hear Thou Me, for I am the Angel of PTAH-APOPHRASZ-RA: this is Thy True Name, handed down to the Prophets of KHEM.

Crowley identified himself with Ankh-af-na-khonsu. He wrote the so-called short "Comment" to The Book of the Law using that identity. In the original ritual that Crowley turned in to "Liber Samekh", the first quoted line read: "I am Moses Thy Prophet, unto whom Thou didst commit Thy Mysteries, the Ceremonies of Israel." The ritual instructions say to substitute Moses with the aspirant's own magical motto and Israel for their own Magical Race. Earlier in the ritual, Apophrasz was described as "the Truth in Motion" i.e. the Voyager.

The Great Invocation" has:

"By the mysterious spell of the dead Lord of Khem: by its miracle revelation unto the Beast, The Prophet of the Sun."

The parallels with the Wake passage from p. 593 appear undeniable though I stop short of asserting Joyce knew Thelema that well to make the parallels intentional. Joyce does have a Prophet of the Sun speak and he does describe this Prophet as an "eversower seeds of light" which alludes to Khem. Aleister Crowley, in his altruistic activities, also perfectly fits the description of an "eversower seeds of light."

Stay tuned for the next episode which will go into some of the Bardo/Book of the Dead influences found in the work of Robert Anton Wilson who was deeply influenced by both Joyce and Crowley.

Finn MacCool, the giant sleeping in the Irish landscape